Archive

Monthly Archives: November 2012

Monthly Archives: November 2012

Now that I think about it, Batman Begins has a shockingly similar premise to Crime and Punishment. As Raskolnikov does, Batman decides to commit crimes (vigilantism), but justifies it on the grounds that it will prevent worse evils. The antagonist in the story presses him to take this rationalization to its logical (but evil and therefore tragic) end point. Batman sees the trap and avoids it, while Raskolnikov falls into it, so Raskolnikov becomes a tragic hero, while Batman becomes a superhero.

Remember that the hero and the villain, or the protagonist and antagonist, often have parallel journeys. In the mythic sense, the antagonist is the dark side of the hero: either his mirror, his complement or his opposite.

|

| Evil Counterparts of Flash, Superman, Wonder Woman and Batman. |

In comics, science fiction and fantasy, this can even be literally true: the heroes face their own evil counterparts, or selves from a parallel universe, or evil self magically or technologically split from themselves.

One of the best sf stories of all time, The Forbidden Planet, captured this perfectly. First of all, despite the fact this movie was made in the 50s without CG, the monster was frickin’ scary. But this was no simple monster movie. And not just because of the similarities to The Tempest.

(Spoilers for The Forbidden Planet follow.)

Commander John Adams (the hero, played by a buff, young Leslie Nelson) and his crew arrive on a distant planet to check on the colonists there. They find all the colonists dead except for Morbius (what a classy villain name!) and his gorgeous, nubile daughter. A creepy, seemingly all-powerful monster that defies the laws of known psychics killed off all the other colonists, and now starts killing off Adams crew.

|

| It’s even scarier when invisible. |

Morbius is surprisingly sanguine about the deaths, busy as he is studying the fantastic technology left on the planet by a dead civilization, the Krell, as he explains to Addams:

Dr. Morbius: In times long past, this planet was the home of a mighty, noble race of beings who called themselves the Krell. Ethically and technologically they were a million years ahead of humankind, for in unlocking the meaning of nature they had conquered even their baser selves, and when in the course of eons they had abolished sickness and insanity, crime and all injustice, they turned, still in high benevolence, upwards towards space. Then, having reached the heights, this all-but-divine race disappeared in a single night, and nothing was preserved above ground.

|

| Innocent Altaira lives in the paradise created by her father with Krell technology. |

Doc is the first crew member to try Krell “brain enhancing” technology. It overpowers his puny human brain and kills him, but not before he has a critical insight:

Doc Ostrow: Morbius was too close to the problem. The Krell had completed their project. Big machine. No instrumentalities. True creation.

Commander John J. Adams: Come on, Doc, let’s have it.

Doc Ostrow: But the Krell forgot one thing.

Commander John J. Adams: Yes, what?

Doc Ostrow: Monsters, John. Monsters from the Id.

Commander John J. Adams: The Id? What’s that? Talk, Doc! [Doc slumps and dies]

Morbius and his daughter are never attacked by the monster. But that changes after Altaira falls in love with Addams. Suddenly, the monster comes after her as well. As the couple and Morbius all flee deeper and deeper into the ruins of the Krell city, Addams finally confronts Morbius.

Commander John J. Adams: What is the Id?

Dr. Edward Morbius: [frustrated] Id, Id, Id, Id, Id! [calming down]Dr. Edward Morbius: It’s a… It’s an obsolete term. I’m afraid once used to describe the elementary basis of the subconscious mind.

Commander John J. Adams: [to himself] Monsters from the Id… Monsters from the subconscious. Of course. That’s what Doc meant. Morbius. The big machine, 8,000 miles of klystron relays, enough power for a whole population of creative geniuses, operated by remote control. Morbius, operated by the electromagnetic impulses of individual Krell brains.

Dr. Edward Morbius: To what purpose?

Commander John J. Adams: In return, that ultimate machine would instantaneously project solid matter to any point on the planet, In any shape or color they might imagine. For *any* purpose, Morbius! Creation by mere thought.

Dr. Edward Morbius: Why haven’t I seen this all along?

Commander John J. Adams: But like you, the Krell forgot one deadly danger – their own subconscious hate and lust for destruction.

Dr. Edward Morbius: The beast. The mindless primitive! Even the Krell must have evolved from that beginning.

Commander John J. Adams: And so those mindless beasts of the subconscious had access to a machine that could never be shut down. The secret devil of every soul on the planet all set free at once to loot and maim. And take revenge, Morbius, and kill!

Dr. Edward Morbius: My poor Krell. After a million years of shining sanity, they could hardly have understood what power was destroying them. [pause] Yes, young man, all very convincing, but for one obvious fallacy. The last Krell died 2,000 centuries ago. But today, as we all know, there is still at large on this planet a living monster.

Commander John J. Adams: Your mind refuses to face the conclusion.

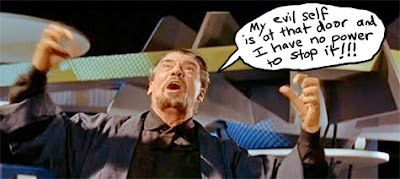

At last, Morbius recognizes the monster.

|

| I feel like this ALL THE TIME. Especially faced with chocolate. |

If you are writing a heroic story, in the end, your hero will succeed and your villain will fail because his own dark side will do him in. In a tragedy, the hero will fail because his own dark side will do him in. A tragedy, in a sense, is just a story told from the point of view of a villain. In a tragic as much as in a heroic story, evil never wins. There is only one genre in which evil wins, and it can still be a satisfactory story: satire or farce. Farce is a more satirical form of comedy. Since satire and farce invert norms for humorous effect, evil wins and good guys end up losers.

(Please do me a favor if you write something like that, and make it clear that’s what you’re doing from the start. I read Alan Clement’s Rogue Nation [spoiler alert] thinking it would be a heroically told thriller, and indeed it was told that way throughout most of the book. At the end, however, to be “clever” (blegh) the author revealed the whole thing was a farce, a mere satire about politics. The good guy came out looking like an moron and a loser, and every single other character in the book were revealed to be schmucks…but clever schmucks, who succeeded in getting everything they had wanted all along. The book wasn’t funny (as satire should be) and it wasn’t satisfying either. But it was published, so what do I know?)

The other thing to remember is that the villain is the hero of his own story. Therefore, you can use a No Fail Story Formula for the villain just as well the hero:

If you prefer these Tips as an ebook you can buy it here for $0.99:

|

||||

Tolkien: “So at the end, Frodo sells the ring and uses the money as a downpayment on a luxury timeshare.”

C.S. Lewis: “Maybe you should give the ending more thought.”

These are my personal tips for NaNoWriMo. You know the drill. Take only what works.

If you prefer these Tips as an ebook you can buy it here for $0.99:

Ink in the Book: Workshop Day 3: Plotting Basics: It’s time for some CPR – Conceptualize, Polish, and Revise. No matter where you are on the road of writing, unless of cou…